“The arrangement of the first exhibition by the Vereinigung bildender Künstler Oesterreichs (Secession) [Association of Visual Artists in Austria] has now nearly reached its completion”, announced the “Neues Wiener Journal” on 25 March 1898. The newspaper also reported that “in a case of censorship that entertains the uninvolved, the Secessionists have been afflicted at the eleventh hour: their poster has been confiscated. The designer of this poster, president of the association Gustav Klimt, has been forced to make changes. A comparison of the two sketches will enlighten and amuse the audience.”

The poster created by Gustav Klimt for the first exhibition of the Vienna Secession is, according to art historian Rainer Metzger, “the graphic work that is probably associated most readily with his [Klimt’s] name even today”[1]. The story behind the genesis of this placard was and is repeatedly mentioned in the wealth of literature on Klimt, and in addition to the definitely proven facts there are also frequent speculations that are occasionally larded with half-truths and untruths. The design of the original draft is often presented as a deliberate provocation by an insurgent artist in the face of a thoroughly straitlaced and conservative society that in turn responded with prohibition of the behaviour displayed by the nonconformist “revolutionary”. However, Gustav Klimt was not actually a social outsider at the time, but rather an artist who was widely respected, particularly among the official authorities. It was not by chance that Emperor Franz Joseph granted an audience to him and his colleagues Rudolf von Alt and Carl Moll from the Secession[2] at which the ideas behind a new artists’ association were able to be explained to the monarch. On 5 April 1898 the Emperor then visited the exhibition, and during the viewing he expressed “on repeated occasions his satisfaction with what he had seen”[3]. The extent to which Gustav Klimt was a recognised member of the Austrian establishment during this time is also shown by his membership of the “committee for the construction of an anniversary church for the Emperor”, whose purpose was to collect donations for a building to mark the 50th anniversary of the Emperor’s accession to the throne.[4] Besides Klimt, only a small handful of other artists belonged to this group, which consisted above all of members of the high aristocracy and representatives from industry and the high clergy.

The censorship of Klimt’s poster is indeed not to be rated as a reaction that was typical of the time; on the contrary, a lack of understanding was shown by many contemporaries and in particular in most of the media. It is likely that the events were due to – as will be explained in more detail later – a very special personnel configuration in Vienna’s Public Prosecution Department that was responsible for the action.

Ever since the departure of this group of artists from the Künstlerhaus, the “Vereinigung bildender Künstler Secession” had been characterised not just by an unswerving feeling for artistic quality, but also by remarkably professional and – from a present-day perspective as well – highly modern media work. Around 19 March 1897, which was still before the association was founded officially, the group’s secretary Alfred Roller noted the following in the minutes: “The letters and other written communication from the V[ereinigung] b[ildender] K[ünstler] Ö[sterreichs] should bear an emblem that always remains the same; the VbKÖ posters should be given a new design each time; the letterhead and the posters should display the words ‘ver sacrum’ each time as a recurring theme; a competition will be advertised in order to receive suitable designs (once for the letterhead, repeatedly for the poster), in which all full members will participate. Entries should be submitted 14 days from the date of advertising.”

One entry in the minutes by Alfred Roller related directly to the poster competition: “We will allow each revered member to choose the size and format of the poster at their discretion and merely ask for the designs to be bedight with as few colours as possible, and for the intended size of the poster to be stated in the case of smaller sketches.” The poster designs were to be sent to Carl Moll within just 14 days. Whilst for the “letterhead the choice should be made once and for all”, it was envisaged that the “suitable poster designs should be used in succession”.[5]

This short note also explains why the Secession posters were initially without any direct reference to the content of the exhibitions. Produced in reserve, as it were, they dealt with the battle of the new way against the conservative old way in various symbolic images, with the association’s word mark “ver sacrum”, the sacred spring, frequently presented in different visual forms.

On 21 June 1897 a vote on the Secession emblem was held among the association’s working committee. There were six entries – further details seem not to have survived – with the design by Kolo Moser being the final choice. His design adopted the old painters’ guild symbol and symbolised the areas of painting, sculpture and architecture in this form with the three shields. Owing to the sparse source material surviving today, it can no longer be determined whether the poster for the first exhibition of the Secessionists was selected in the course of this competition, or whether Gustav Klimt was awarded the job by virtue of his office as president of the association.[6] What is certain is that Kolo Moser also designed a poster whose original version has survived.[7]

On 21 July 1897 the association founded its own “press committee” whose members were Kolo Moser, Rudolf Bacher, Felician von Myrbach and Alfred Roller.[8] The group was apparently highly effective: the individual steps for increasingly strengthening the group – including an audience with Emperor Franz Joseph, the announcement of the first exhibition, and also the construction of the Secession building – were accompanied by numerous favourable press reports whose consistent similarity and frequently identical formulations are a sign that corresponding press releases were dispatched as well.

On 2 March 1898 the following comment was published in the “Arbeiter-Zeitung”: “The Vereinigung bildender Künstler Oesterreichs has taken possession of the horticultural society building and immediately set to work adapting the rooms for the first exhibition. At the same time, pre-announcements have appeared on street corners for the first exhibition that will be on view between the end of March and mid-June 1898. The Secession poster that has been drawn by its president Klimt will only be put up directly prior to the exhibition opening. It is planned that the foundation stone for the future Secession exhibition building, to be constructed near the Academy of Fine Arts and next to Wienzeile, will be laid at the beginning of April.”[9]

Slightly more information on this initial “exhibition pre-announcement” was provided in the “Neuigkeits-Welt-Blatt” dated 25 March 1898. The article reads: “The current posters with the three green shields which are supposed to symbolise the green art of the ‘young ones’ or the hopeful green in the three visual arts, will be replaced by a poster created by Klimt.”[10] Strangely, the affiche with the three green shields has not survived in any public collection, but the description could suggest that it was an adaptation of Kolo Moser’s letterhead logo that was also used in advertisements for the Secessionists.[11]

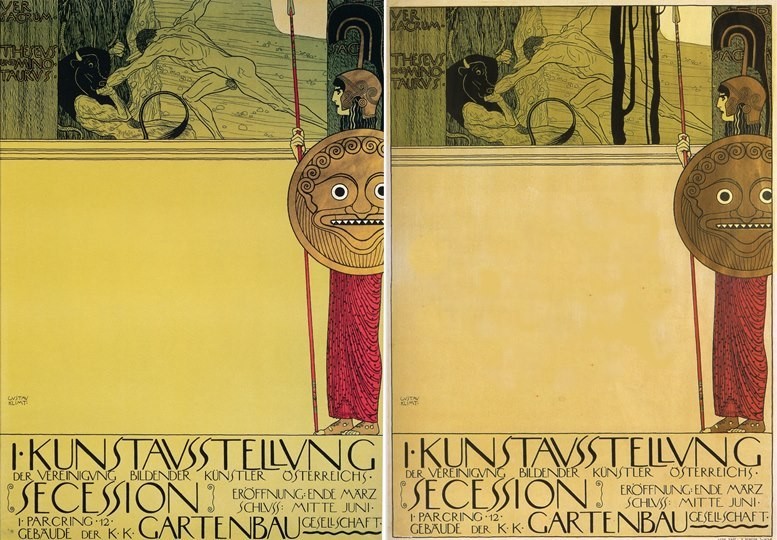

Gustav Klimt, posters for the first exhibition of the Vienna Secession, uncensored and censored versions, 1898

Numerous newspapers mentioned the planned Secession poster by Gustav Klimt in texts that were for the most part identical[12], and the reaction in the media was similarly considerable when – shortly before the exhibition opening – the use of the affiche in its original form was prohibited by the censors: “Theseus, who wrestles down the Minotaur, was inappropriately clothed in the opinion of the censorship authorities, even though he was wearing the customary fig leaf. The full print run of posters fell victim to the confiscators, and as they did not have enough time to produce new posters, the Secessionists were forced to cover Theseus with thick stripes. Incidentally, the public had the opportunity to view the original sketch of the poster in the March issue (3.) of the journal ‘Ver Sacrum’.” [13] This action taken by the censors against a work with an orientation on classical art was criticised among culture enthusiasts and brought many ironic comments in the newspapers. For instance, the newspaper “Pester Lloyd” published in Budapest commented on the events in Vienna as follows: “It is odd that the Secession has suffered a defeat even before the commencement of its campaign – at the hands of the censors. Klimt drew a splendid poster for them, on which Theseus, advancing boldly, slays a quite bull-like Minotaur. This Theseus was too undressed for the censors’ tastes! Although he was equipped with the entirely standard fig leaf, even that fig leaf seemed too repulsive to the virtuous censors and they prohibited use of the poster. This is a first in the history of censorship, as the leaf of the fig tree has always been viewed as the symbol of chastity. So Klimt has been compelled to paint a couple of tree trunks in front of Theseus, one of which completely hides the fig leaf. This happened in … really in Vienna, and not somewhere like a provincial backwater.”[14]

The time and effort needed as a direct result of the censorship was not inconsiderable in view of the short amount of time available for correcting the posters. For instance, there is evidence of at least two different sizes of the poster that had to be “toned down”.[15] Three sizes of the censored version have survived.[16]

The social democratic “Arbeiter-Zeitung” held Vienna’s press prosecutor Dr Karl Bobies (also Carl August Bobies, 1853–1922) responsible for the censorship[17]; he was the subject of intense criticism on regular occasions owing to his confiscation of the “Arbeiter-Zeitung” and other newspapers, with his controversial measures even triggering extensive critical parliamentary debates.[18] For example, in 1898 alone Bobies ordered the weekly newspaper “Extrapost” to be confiscated five times because it published Émile Zola’s novel “Paris” in instalments and prosecutor Bobies found several sections that repulsed him. As many as six weeks before Klimt’s poster was censored, the “Arbeiter-Zeitung” remarked “that Dr Bobies is a thoroughly unsuitable person to carry out the duties of a press prosecutor in Vienna”.[19] It is remarkable in connection with Klimt’s censorship that Karl Bobies was a cousin of the painter Carl Bobies, who was a member of the Vienna Künstlerhaus from 1865 until his death in 1897. The question whether this “family closeness” to the Künstlerhaus influenced the attitude of the prosecutor towards the Secession must naturally remain unanswered.

In literature on Gustav Klimt it has been repeatedly speculated why the poster was censored on the one hand, yet on the other hand publication of its original version was possible in the journal “Ver Sacrum”. The answer to the questions that have surfaced over and again in this connection is revealed if one looks at the legal fundament: the background to this event was given by the 1862 Press Act, which came into force on 9 March 1863.[20] This Act granted freedom of the press to the extent that there was no pre-censorship for printed materials. However, posters were subject to stricter regulations than books and journals. Paragraph 23 specified that “displaying or advertising printed material in the streets or in other public places without the express permission of the security authorities is forbidden”. Exempted from this regulation were “announcements purely of local or commercial interest” such as “theatre flyers, announcements of public merrymaking, of lettings, sales, and the suchlike”. Even these announcements were “only permitted in specific places as determined by the authorities”. This explains why it was possible to prevent the distribution of a poster in advance, whereas legal proceedings could only be brought against a journal after it had been published – although this did not happen in the specific case of the depiction of Klimt’s poster in “Ver Sacrum”.

No material has been found on the treatment of the posters according to Paragraph 23 of the Press Act despite painstaking research at the following institutions: Archiv der Secession Wien, Künstlerhaus-Archiv, Niederösterreichisches Landesarchiv, Polizeiarchiv Wien, Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv.[21] For this reason, it has so far not been possible to evaluate any filed documentation on the censorship of Klimt’s poster. Nevertheless, the summary of all existing sources on this incident shows that there are many clichéd approaches to this item in Klimt’s oeuvre that must be amended.

Denscher, Bernhard: Censored: Gustav Klimt, in: Denscher, Bernhard (Ed.): Viennese Posters. Art, Artists, Artwork. 1868–1938), Wolkersdorf 2022, S. 40ff.

Translation: Rosemary Bridger-Lippe

[1] Metzger, Rainer: Gustav Klimt. Das graphische Werk, Vienna 2005, p. 44.

[2] Neues Freie Presse, 11 March 1898, p. 6; NeuigkeitsWeltBlatt, 12 March 1898, p. 3.

[3] Neues Wiener Journal, Abendblatt, 5 April 1898, p. 3.

[4] Das Vaterland, 19 March 1898, p. 1; Danzers Armee-Zeitung, 24 March 1898, p. 5; the project is the Franz-von-Assisi church that now stands at Mexikoplatz in Vienna.

[5] Pausch, Ottokar: Gründung und Baugeschichte der Wiener Secession, Wien 2006, p. 87f.

[6] There are no relevant documents in the Vienna Secession Archives, according to information from Mag. Tina Lipsky on 16 January 2018.

[7] Leopold, Rudolf – Gerd Pichler (eds.): Koloman Moser 1868–1918, München 2007, p. 56.

[8] Pausch, Ottokar: Gründung und Baugeschichte der Wiener Secession, Wien 2006, p. 146ff.

[9] Arbeiter-Zeitung, 2 March 1898, p. 6.

[10] Neuigkeits-Welt-Blatt, 25 March 1898, p. 10.

[11] Oesterreichisch-ungarische Buchhändler-Correspondenz, 15 January 1898, p. 10.

[12] Cf. for example: Neue Freie Presse, 2 March 1898, p. 7; Arbeiter-Zeitung, 2 March 1898, p. 6; Das Vaterland, 2 March 1898, p. 7; Deutsches Volksblatt, 2 March 1898, p. 9; Dillinger’s Reise- und Fremden-Zeitung, 20 March 1898, p. 6.

[13] Neue Freie Presse, 25 March 1898, p. 8.

[14] Pester Lloyd, 25 March 1898, p. 2.

[15] Small, uncensored: Albertina 69.5 cm x 53 cm Mascha 8, DG 1994/152 (olive green version); Museum of Applied Arts 64 x 46.5 Pl 1658 (pink version); large, uncensored: Albertina 97 x 69.5 / DG 2004/8585 Wien Museum 96.8 x 69.8 / HMW 129001/1 (both olive green).

[16] Very small, censored: Wien Museum 40 cm x 29.5 cm / [Cat. Vienna around 1900, 1964] (olive green); small, censored: Galerie St. Etienne (Art Basel 2017) 63 x 45.5 (olive green); Wien Museum 63.5 x 47 / [Cat. Vienna around 1900, 1964] (pink); Musée de la Publicité, Paris 64 x 47 / Inv. 19838 (pink) The Museum of Modern Art 63.5 x 46.9 / 207.1968 (pink); large, censored: Albertina 96 x 70, DG 2003/535; German Historical Museum 95.2 x 67.5 / P 73/2855; Wien Museum 97 x 70 / HMW 129001/2; Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Kupferstichkabinett 97.3 x 70 / Inv. No. A 1898-479 (all olive green).

[17] Arbeiter-Zeitung, 27 March 1898, p. 4.

[18] Cf. for example: Reitzer: Der prüde Staatsanwalt, in: Novitäten-Anzeiger für den Colportage-Buchhandel nebst Mittheilungen für Buchbinder u.s.w., 15 November 1898, p. 1. For the debates in Parliament, see: Arbeiter-Zeitung, 2 April 1898, p. 1 and Arbeiter-Zeitung, 16 December 1898, p. 1.

[19] Arbeiter-Zeitung, 17 February 1898, p. 1.

[20] Reichsgesetzblatt für das Kaiserthum Oesterreich 1863, No. 6.

[21] Many thanks go to the staff at all these archives for their help and assistance in this respect.