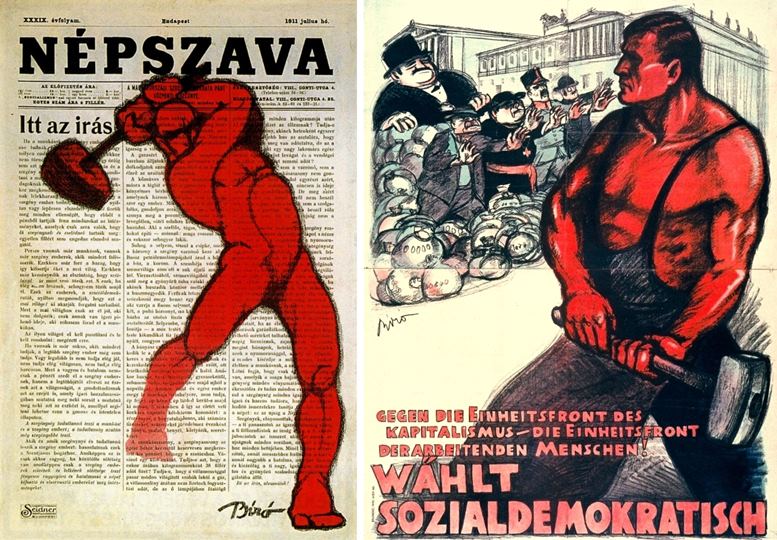

In Austria, political posters were in existence before the First World War, but they were essentially just filled with text. It was a different story in Hungary: here, the graphic designer Mihály Biró was particularly notable as he created spectacular illustrated posters for Hungary’s Social Democratic Party from 1910 and would later become critically significant for Austria as well. In particular, his poster with the red man for the newspaper “Népszava” from the year 1912 became a model of visual political propaganda whose influence extended far beyond the Hungarian borders.[1]

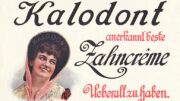

In Austria, on the other hand, the situation was not as advanced: even when the First World War broke out, the use of illustrated posters for political purposes still developed rather hesitantly. Patriotic propaganda arrived on billboards via an indirect path. Pictures of cheering soldiers and phrases such as “Back home for Christmas” serve as evidence of the uninterrupted euphoria at the beginning of the war. Advertising in the year 1914 also reflects this fatal underestimation of the danger involved: the topic of war was still firmly in the hands of the entertainment industry. The extent to which media perception was so distanced from the cruel reality is shown especially clearly in an announcement by Vienna’s Apollo Variety Theatre that advertised a show in which costumed dogs presented “comical scenes” from military life. However, the industry also made serious attempts at patriotic statements. For instance, the poster for a performance in the famous Musikvereinssaal in Vienna showed the brotherhood in arms being sworn between Germans and Austrians, in the form of a declamatory handshake between a German and an Austrian soldier.

Left: Anonymous, 1914 / Right: Fritz Gareis, 1914

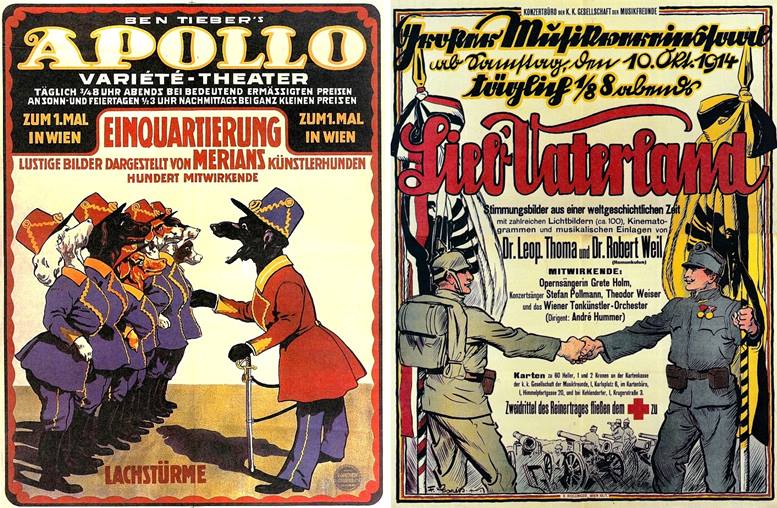

Right from the start of the war, it was clear that the authorities in Austria did not embrace visual propaganda to the same extent as other warring powers. The Emperor told “his peoples” (“An meine Völker!) what to do using condescending expressions, and it seems to have been below his imperial dignity to ask for their commitment. Patriotism was an obligation of all citizens, and there was the belief that reassurance was not really necessary. Although there was the “war press bureau”, where a number of writers and creative artists were able to fulfil their “military obligation” in a cosy and safe environment, this focused primarily on press work and a kind of “artistic idealisation” of war. Actual poster propaganda developed indirectly and was driven by various institutions, such as charitable associations. For example, one of the first propagandist war posters in Austria was an advertisement for an art exhibition whose sole motif was Emperor Franz Joseph. During the initial months of the war, the picture of the Emperor was a common image. It was supposed to represent the meaningful commonalities between the many different peoples of the monarchy. After war had been declared, huge pictures of the Emperor were carried through the streets of Vienna in the various public rallies, together with the monarchy’s black-and-yellow flags.[2]

Left: Adolf Karpellus, 1914 / Right: postcard, ca. 1914

Thousands of postcards, stamps and calendars with the portrait of the Emperor were published – frequently together with the picture of the German Emperor, Wilhelm.

Although the monarch’s portrait was an everyday item at this time, it also became increasingly taboo. His picture seemed to be only authorised for use in official and ceremonial settings. It appears that posters that exposed his likeness to the harsh life of the streets were seen as a medium that did not befit the rank of a monarch. For example, this poster only shows a sculpture of Franz Joseph, and not the Emperor in person. From those years, hardly any posters have survived that display the Emperor’s actual picture, such as on the many postcards. Indeed, the official public authorities were very reticent when it came to street advertising with its broad impact; war propaganda was primarily organised by private entities.

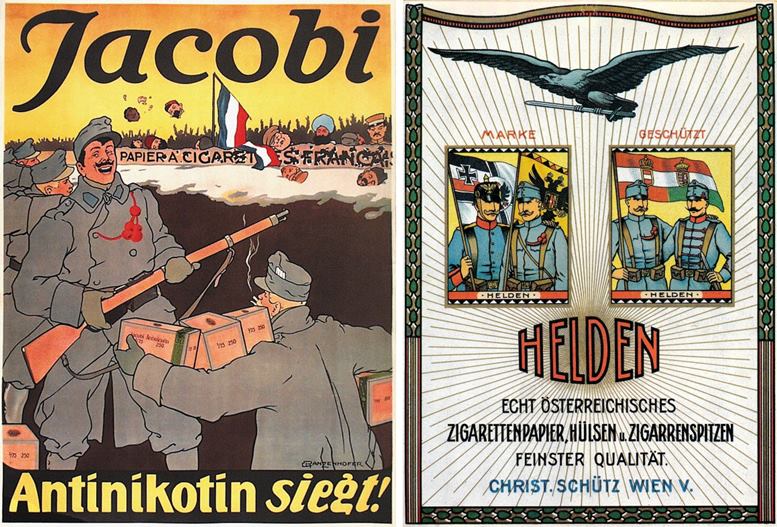

Left: Emil Ranzenhofer, 1915 / Right: Anonymous, 1914

Besides the event scene, it was predominantly commercial advertising that was responsible for such propaganda, such as this poster for cigarette paper that advertises the brand “Helden”, meaning heroes, and evokes the Austrians’ military ties with Germany and Hungary in its illustrations. Another poster for cigarette paper shows that extremely brutal images were used in an attempt to win customers. The affiche blatantly highlights the economic component of the war, because the actual opponent here is not so much France, but the French rival product.

Both posters: Adolf Karpellus (Left: 1916 / Right: 1917)

Propagandists who were close to the state were far more reticent; the most conspicuous among the advertising media were the posters that advertised sales of war bonds. Illustrated posters were only used from the second bond issue in May 1915 onwards. At first individual banks were responsible for that, but as of the third bond issue in the autumn of 1915, such affiches were also produced by official state institutions. Prestigious artists were entrusted with this responsibility, and they developed various image strategies in order to develop positive visualisations for the war and therefore for the product on sale, the “issue of wartime bonds”. One common method used in Austria was downplaying the terrible reality of the war by shifting events back into earlier centuries. Heralds with flying colours and knights on horseback cavort around, while in the reality of war thousands of soldiers were dying in artillery fire and in machine gun attacks.

Left: Maximilian Lenz, 1917 / Right: Poster published by the Parliamentary Recruiting Commitee, June 1915

There are repeated references to Christian Medieval iconography, and war is visually presented as a battle between knights and dragons. The two British writers David Bownes and Robert Fleming observe: “The use of medieval knights to represent national virtues was especially popular in Germany and Austria, where such images drew on a rich tradition of folklore and historical fact.” [3]

An interesting example shows that there were obviously also influences that extended beyond the front lines. In 1915, for example, a recruitment poster was used in the UK that showed St. George fighting the dragon – the victory of good over evil. Two years later, the Austrian graphic designer Maximilian Lenz took up this motif in a very similar style. It is difficult to believe that Lenz had not come across the British poster, as the visual structure of his poster is so similar to the British one. And it is an astonishing fact that examples of enemy visual propaganda were actually on view during the war at exhibitions in Vienna, such as in early 1917 in the “Exhibition of wartime graphics” at the Museum of Applied Arts.[4]

Left: Alfred Roller, 1917 / Right: Paul Suján, 1917

Besides the trivialising historical images, there were also occasional posters that displayed realistic representations of the war. In Austria these were seldom borne by martial pathos, however – their proximity to reality rather appealed to the sympathy of observers. The sobering feeling among the population, to which the initial enthusiasm for war had soon given way, is documented by posters such as for the 7th war bond issue which poses the question “Und Ihr?” (And You?). Advertising for social areas occasionally adopted an even blunter approach, as can be seen in the poster for a wartime benevolence exhibition in Bratislava. In the context of totalitarian National Socialist propaganda during the Second World War, such pictures would have been absolutely inconceivable.

Left: Ernst Ludwig Franke, 1918 / Right: Kurt Libesny, 1918

It is understandable that the reality of the war brought increasing war fatigue amongst the population. The posters for war bond issues that appeared at a later stage addressed this longing for peace very clearly, with frequent new images. For example, a farmer shows how you can sow peace with money for the war bond, or two Austrian soldiers open a heavy steel door leading to peace. Another picture shows soldiers and families reuniting against the skyline of Vienna, addressing the eagerly anticipated desire of millions of people during this difficult period. Compared to the poster propaganda of the Allies, the Austrian advertising was astonishingly reticent. This becomes particularly clear if you take a look at the accelerated propagandist attacks by the US on its opponent Germany, for example.

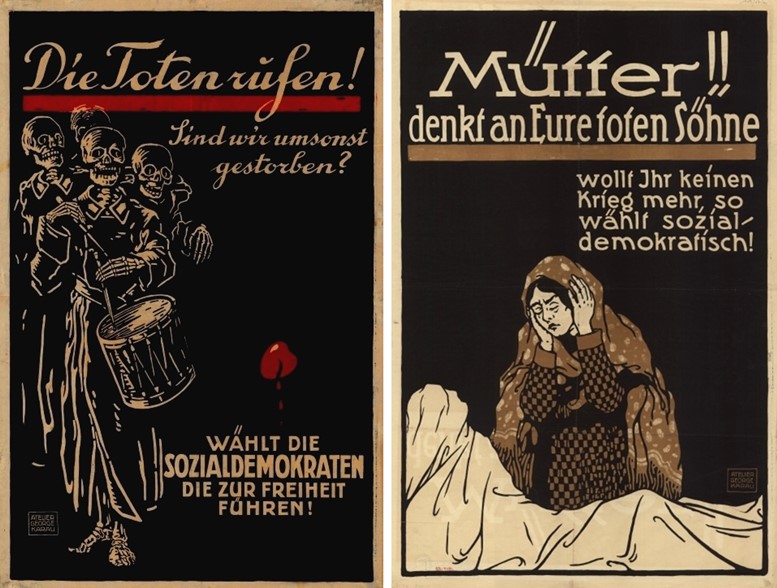

So what was the source of the acrimony in the political visual imagery of Austrian election campaigns after the First World War? The primary influence of the posters during the First World War on developments in the post-war era was not its aggressive visual language, but the fact itself that visualisation of political content was now practised as well. Another important aspect in the development of media was the abolition of any kind of censorship in a resolution by the Austrian National Assembly on the 30th of October, 1918. This measure freed the media from the constraints of wartime censorship, but it also enabled unrestrained propagandist disputes that occasionally led to the extreme disparagement of political opponents, even going as far as anti-Semitic rabble-rousing.

Both: George Karau, 1919

On the 16th of February, 1919 the first free democratic elections took place in Austria in which women were entitled to vote. One spectacular new development in these elections was the mass use of illustrated posters. An article in the “Neue Freie Presse” with the title “Die Bildergalerie der Straße” (The street picture gallery) writes: “The illustrated election poster attaches its signature to the election week. The text merely supplements the image, though. The picture dominates, striving to achieve a sole and independent effect. It reckons on the psychological fact that cinema has gained higher priority over theatre. This has prompted a contest among poster designers to see who can deliver the briefest and most sparing comment.”[5] And a few days later, “Das interessante Blatt” comments: “A good era for poster designers. There are certain truths to be found in the political thought behind the images. It is high time for collectors to embark on a collection of election posters because they will disappear again after the elections.”[6]

The affiches of the Social Democrats focused not so much on their political rivals, but rather on attempts to come to terms with the recent past. Their main rivals, the Christian Social Party, borrowed from the visual aesthetics of the First World War with its poster of the soldier returning home, although it portrayed its left-wing opponent as a bomb-throwing pyromaniac and red terrorist.

Left: Franz Griessler, 1919 / Right: Fritz Schönpflug, 1919

The posters of the “Bürgerlich Demokratische Partei” were one particular phenomenon in this propagandist dispute. This small group of liberals were committed to becoming a critical third force in Austria. In order to achieve this, they spent by far the most on materials for their election campaign compared to any of the other parties, and the group also had the largest number of illustrated posters, for which they hired graphic designers who were accomplished in advertising. The supposed perilous nature of the two major parties was repeatedly illustrated in new visualisations. Here, for example, the red devil is leading the people into the abyss together with the Catholic priest. Despite this huge expenditure, the election result was more than disappointing for this party of liberals.

Theo Matejko, 1919

A year later, in 1920, Austria had more national elections: graphic designers at the time received key stimulus from Mihály Biró’s work for the Social Democratic Party. For these elections he resurrected his red man from before the war, and drew him in various conflict situations. The repeated theme was the fight of the workers against a united front of reactionaries, who were portrayed as a clergyman, imperial general, capitalist and major landowner. At one point they attempt to refuse him entry to parliament, then they want to prevent him from ridding the country of the refuse of the monarchy.

Left: Mihály Biró, 1912 / Right: Mihály Biró, 1920

The aggression in the visual rhetoric of these post-war years stems – as already mentioned – not so much from the visual imagery of the Austrian posters in the First World War: it is due to the general aggression in the political dispute of that era. Role models were found in political cartoons and above all on international posters. For instance, the “red giant” created by Mihály Biró played a significant role in the general elections of 1920, as is shown in three examples from different parties. The Christian Social Party’s giant protects the people from the capitalists, who want to lead them into the abyss together with a socialist, recognisable by his “liberty cap”. Portrayals of the bourgeoisie confirmed – in line with that party’s ideology at the time – to anti-Semitic caricature templates.

Left: Hanns Zehetmayr, 1920 / Below: Alois Mitschek, 1920 / Right: Mihály Biró, 1920

The Communist Party poster looks like a pamphlet from the political right wing in its fight against the leftists. Holding a flaming torch in one hand, the “red giant” crushes the parliament building on the way to proletariat dictatorship, while the Social Democrat “Superman” attempts to gain entry to Parliament against resistance from the reactionaries. Using the same symbolic figure, these examples highlight the different ideological positions of the parties. They also show that at times posters are able to document the atmosphere and mentalities of an epoch more clearly than any other source.

[1] Horn, Emil, Mihály Biró, Hanover 1996 (=Reihe internationale Plakatkünstler).

[2] Fremden-Blatt, 28 January 1914, p. 11.

[3] Bownes, David – Robert Fleming, Posters of the First World War, Oxford 2014, p. 90.

[4] Denscher, Bernhard, Gold gab ich für Eisen. Kriegsplakate 1914–1918, Vienna 1987, p. 81; Kunstchronik und Kunstmarkt, 6 April 1917, p. 284; Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 9 March 1917, p. 8.

[5] Neue Freie Presse, 15 February 1919, p. 13.

[6] Das interessante Blatt, 20 February 1919, p. 9.

Translation: Rosemary Bridger-Lippe

Lecture at the international conference „Visualizing Cataclysm and Renewal. Visual Culture and War Representations in Central and Eastern Europe in World War One and its Aftermath (1914–1920)”, May 29 – 31,2019, Budapest.